This month, the heads of the two Art subject associations consider the future of Art and Design education in schools. Paula Briggs, CEO and Creative Director of AccessArt, surveys the current landscape and reflects on what’s vital for Art education now. And Michele Gregson, General Secretary/CEO of the National Society for Education in Art and Design (NSEAD) asks what a curriculum fit for the future with learners and communities at its heart should look like.

Paula Briggs from AccessArt on the importance of a value narrative for Art education

As a charity and Subject Association for Art, there are two key questions which drive our work. The first is aspirational: “What do we want Art education to become?” whilst the second stays firmly grounded in the present: “What can we do in schools, right now, to make a difference?”

We believe it’s vital that as many of us as possible engage in both these questions to ensure we offer pupils a fit for purpose Art education. But there is a third question which is emerging, which is more urgent, relevant and powerful: “What do we need Art education to be, right now?”

This third question helps us understand that there is an opportunity for us all (as policy makers, educators and parents) to recognise the values, benefits and capabilities a rich Arts education can bring. It also enables us to acknowledge the many issues we currently face. We have seen how the continuing legacy of the Gove-led exclusion of the s from the EBacc has placed increasing pressure on Expressive Arts subjects. The result has been fewer specialist teachers, tighter timetables, and a diminished Arts offer in many schools. As opportunities to develop material and visual literacy decline, children are left with fewer hands-on experiences and inadequate resources, and the foundations of Arts education continue to erode. The downward spiral is steep and accelerating.

Alongside this we are also seeing many more pupils struggling with mental health, often worsened by the relentless pressure of assessment, which in turn affects their ability to focus, engage, and learn. Government statistics show that 17.79% of children are now classed as persistent absentees (missing 10% or more of their sessions)1. Outside school, and as a society, so many of us are experiencing anxiety, fatigue, and sense of fragmentation and disconnection.

Can a rich Arts education help?

For too long government policies have seen Art education as a “cost” – an add-on, an enrichment – something justified only once other subjects are secure. But we should remember that Art education (and Art) can serve us. A rich Art education pays us back as individuals, as communities and as a society. The Cultural Learning Alliance’s Capabilities Framework is an invaluable tool in helping us understand the true purpose of expressive Arts education, especially in today’s climate – providing us with clear recognition of its evidence-based value. A rich and well-supported Arts education is a vital part of helping young people reconnect with learning, with themselves, and with the world around them. Imagine Art education as both a salve and a space. In the face of disengagement, anxiety, and a loss of the love of learning, Art offers a way to pause, reflect, and rebuild.

As a society, we have the power to rethink what we want Art education to be. We can do that at any time – if we choose to. We see schools that are working hard to nurture their Arts offer at grassroots level. These schools invest in their teachers, find creative ways to fund resources, and recognise the unique space the Arts create for a different kind of learning. And these spaces do make a difference to children’s lives. But if we want real change – in the space between practice and policy, between grassroots and blue sky thinking – we must support policymakers to be bold enough to ask the bigger questions and to recognise the real purpose of Art education.

Not all values are monetary, and not all knowledge is measurable.

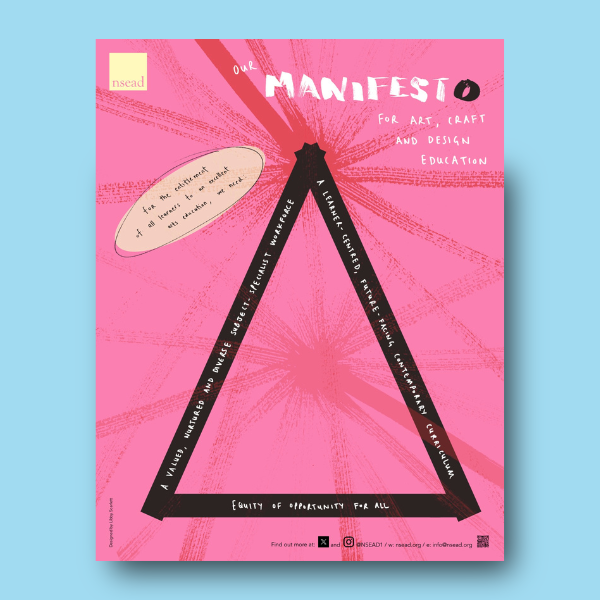

Michele Gregson from NSEAD on a future-facing Art and Design curriculum for every learner, and the central role of the Art-teaching workforce

In a year of intense debate, discussion and consultation over the future of the national curriculum in England, the Arts and culture sector have made a compelling case for creative Arts education, forming an alliance that has shown real strength and delivered a simple, consistent message: the Arts make our lives better, in every way. The value of the creative Arts should not be in question. Allocating time, resources and respect to creative Arts education is an investment in the well-being of our nation. However, whilst some of these issues are in the Government’s gift to address, we need to look at what is happening in our classrooms and the deeper legacy of neglecting the Arts in our schools, and some of the myths that have been ascribed to Art and Design in particular.

To address one myth directly: Art and Design may be a popular choice amongst students, but that does not mean that it is thriving. We urgently need to address the equity and relevance of both national curricula for our subject, and how it is interpreted at school level: learners are having vastly different experiences depending on where they live and what kind of school they attend.

Learners may have quite a different response to the curriculum they are offered depending on their gender, their race and ethnicity – or any educational experience that does not speak to their interests, aspirations and lived experience. Too many children are falling through these gaps, and whilst more time and better resources are needed, we also need to look at the quality of teaching and learning and local curriculum design.

NSEAD members are asking these questions: what does best curriculum practice look like in Art, Craft, and Design? Not in the form of projects or outcomes, but through curriculum purpose, pedagogy and impact, or, more simply: why, what, and how? What does a curriculum, with learners and communities at its heart, look like today and what would a curriculum fit for the future look like? We need a national curriculum that closes the gaps and places value on the things that matter to learners. But we also need the space to allow teachers to determine the values and the ethos for learning in our subject.

It is for teachers, not the government, to select the knowledge, content and processes that are relevant to their learners. A curriculum that allows for plurality of approaches, that allows us to develop the most suitable skills, habits, behaviours and attributes in our learners. These include critical analysis, exploration, and expression in response to visual and other sensory stimuli, and consideration of concepts, issues, themes, and dimensions.

For this to be possible, we need to look beyond the scope of the Curriculum and Assessment Review, to the investment in nurturing our workforce. Teachers need to be able to engage in deliberative dialogue and challenge top-down directives that limit classroom creativity. For this they need time, space, and connection with the professional community.

There are those with vested (sometimes commercial) interest in the de-skilling of our subject specialist teachers, and others who see teachers as merely curriculum operatives rather than the skilled, specialist designers of learning in our subject. Subject Associations offer an essential counterbalance, promoting the interests of learners and those who work with them, leading research and advocacy, and safeguarding the integrity of our subjects. It is more vital than ever that we work together, as a progressive movement, for the sake of every learner.