Jacqui O’Hanlon, Director of Creative Learning and Engagement at the Royal Shakespeare Company, shares the important new findings from research into the impact of Shakespeare’s work and theatre-based teaching on learning outcomes in primary education.

At the RSC, we’ve long been interested in research – from teacher action research to longitudinal studies into the benefits of expressive arts subjects and experiences to young people in schools. One of the sticking points many of us are familiar with is how to measure impact – and even if it’s possible to do so. The argument goes that we only value those things we can measure, and that because expressive arts subjects and experiences are so enmeshed in developing the human psyche, they are too complex and multi-faceted to be measurable.

Through a grant from Paul Hamlyn Foundation, we had the opportunity to undertake research into the impact of Shakespeare’s work and theatre-based pedagogies on learning outcomes. When we asked teachers what kind of research question would be most helpful to them, they said they wanted the data to back up what they saw happening in their classrooms when they used the combination of Shakespeare’s plays and a theatre-based pedagogy.

Across 15 years of working in partnership with primary, secondary and special schools in England, two themes have consistently emerged about the difference that particular combination makes to learning outcomes:

1. Children’s literacy, particularly their writing, improves – they write more, they use more complex language, they want to write (particularly children who have previously been reluctant to write).

2. Children’s academic self-concept improves – when a child feels confident about Shakespeare’s work, they feel differently about their ability to navigate other difficult things. And they think they’re good at learning.

Teachers wanted us to undertake research to understand exactly what was changing for children in these two areas.

What we did and what we found out

Our research fellows, Lynsey McCulloch and Matthew Collins, reviewed existing validated tools used by social scientists to measure language development. They then worked with teachers to develop a writing measure that incorporated those validated tools.

Using a randomised control trail, we recruited 45 state primary schools across England – all with above average eligibility for free school meals – and randomly assigned them to either an intervention or control group.

Teachers in intervention schools took part in five days of professional development with the RSC and delivered 20 hours of Shakespeare teaching to Year 5 pupils using RSC approaches.

Control schools delivered their existing curriculum. Researchers then analysed more than 3,000 written responses from children in control and intervention schools over the 12-month research period.

Findings from RCT

We measured language development in children’s writing, comparing the intervention and control schools. Both groups were responding to a character dilemma from a Shakespeare play where the character was stranded on an island. Overall, we found children in the intervention group, whose teachers had worked with the RSC, outperformed control schools in 98% of indicators.

You can find the results here: Time To Act | Royal Shakespeare Company (rsc.org.uk)

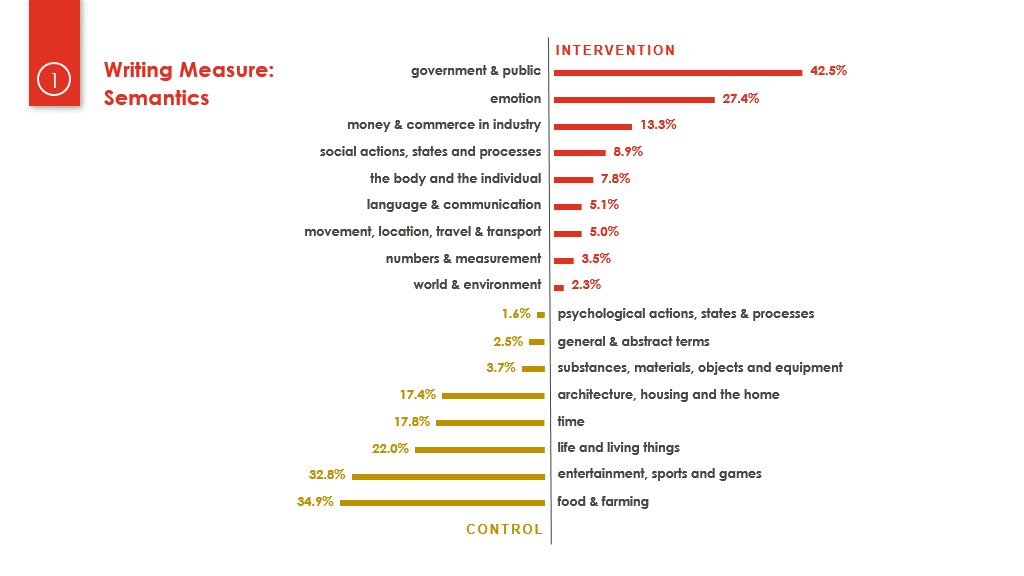

One of the findings we were really fascinated by were the differences we saw in semantics (content) in the children’s writing. Children in intervention schools outperformed control students in the following ways:

- their ability to express emotion through their writing (children in intervention schools used far more words relating to emotion than children in the control schools);

- they demonstrated greater resilience and optimism in their writing (in control groups they could not see a way forward for the character, but children in intervention schools were planning for the future and thinking through how the character could survive on the island);

- they showed greater ability in comprehension and inferencing.

We also used the Myself As a Learner Scale which is already in use in lots of schools. It measures children’s perceptions of themselves as learners and problem solvers. There we saw greatest differences between intervention and control schools with regard to feelings of agency and ability. Top scoring items for children in intervention schools related to feeling they know how to solve problems, feeling confident they are good learners and confidence in language.

They represent the kind of growth mindset we want to develop in children – the sense that they can learn to do anything they want.

Inequity in measurement tools

We also found that some children who were previously considered to be operating below age related expectations (ARE) got some of our best writing results. For example, the child who was considered below ARE because she didn’t join up her handwriting and wasn’t consistent with her full stops. However, when we put her writing through the software it came out near the top percentile in terms of sophistication of words (lexis) and content. In her writing about Juliet at the dance where she meets Romeo, the Year 3 girl wrote lines like:

“… The dress looks like it’s made out of clouds … When she dances, it’s like the stars are taking her to heaven … At parties the more she dances with grace the brighter the stars shine …”

The software we developed enabled the teacher and child to understand her potential in a very different way.

What does this mean?

This means that not all assessment measures meet the needs of a diverse pupil population. And I think it also means that expressive arts subjects can help us understand potential and progress in a way that existing ways of measuring educational attainment don’t. It means that the integration of expressive arts subjects, and measurement tools, can help to provide a more inclusive environment in which children can thrive and flourish.

Professor Pat Thomson shared a wonderful quote recently from Maxine Green, who described an arts-rich education as building a “wide-awakeness to the world.” Another way of framing this is that expressive arts subjects build adults’ wide awakeness to the child; a wide awakeness about what they can achieve – and who they can become.